There are dozens of ways to take stock of the Affordable Care Act as it turns 5 years old today. According to HHS statistics:

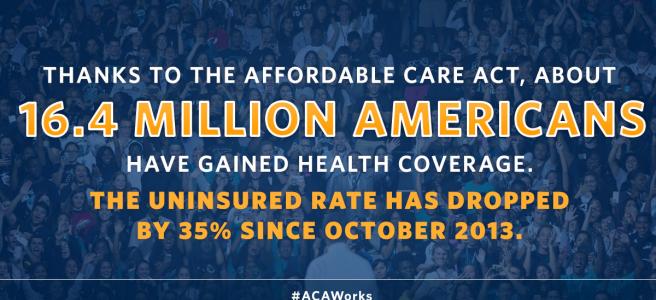

- 16.4 million more people with health insurance, lowering the uninsured rate by 35 percent.

- $9 billion saved because of the law’s requirement that insurance companies spend at least 80 cents of every dollar on actual care instead of overhead, marketing, and profits

- $15 billion less spent on prescription drugs by some 10 million Medicare beneficiaries because of expanded drug coverage under Medicare Part D

- Significantly more labor market flexibility as consumers gained access to good coverage outside the workplace

Impressive. But the real surprise after five years is that the ACA may actually be helping to substantially lower the trajectory of healthcare spending. That was far from a certain outcome. Dubbed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act for public relations purposes, there were, in fact, no iron clad, accountable provisions that would in the long run assure that health insurance or care overall would become “affordable.”

ACA supporters appear to have lucked out—so far. Or maybe, just maybe, it wasn’t luck at all but a well-placed faith that the balance of regulation and marketplace competition that the law wove together was the right way to go.

To be sure, other forces such as the recession were in play—accounting for as much as half of the reduction in spending growth since 2010. But as the ACA is once again under threat in the Supreme Court and as relentless Republican opposition continues, it’s worth paying close attention to new forecasts from the likes of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the actuaries at the Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services (CMS).

The ACA is driving changes in 17 percent of the U.S. economy that, if reversed or interrupted, would have profound impact on federal, state, business, and family budgets. A quick look at some important numbers follows:

Overall spending trend. In 2013 overall healthcare spending increased 3.6 percent, to $2.9 trillion; it was the fifth consecutive year of growth in the range 3.6 to 4.1 percent, according to CMS economists. The share of the economy devoted to health spending held steady at 17.4 percent for the fourth year in a row. To boot, health spending and GDP increased at similar rates from 2010 to 2013. That hasn’t happened in decades.

The causes of the slow down, as cited by CMS:

- The lingering effects of the recession and a modest economic recovery;

- Federal budget cuts (sequestration);

- Slower growth in Medicare services; and

- The shifting of costs to consumers with private insurance, causing them to spend less.

The rate of healthcare spending growth is projected to increase to an annual average 5.7 percent in the period 2014-2023, 1.1 percent faster than projected GDP growth. CMS also predicts that health spending will be 19.3 percent of GDP by 2023.

The causes of the uptick: improving economic conditions; ACA-spurred coverage expansions; and the aging of the population.

Much hand-wringing has occurred around this projected uptick after the welcome 2009-2013 respite. Angst also surrounds the shift of costs to consumers, via higher deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance. But I think we need to bear in mind three important points:

(1) The 10-year health cost/spending forecast is still slower than the average over last four decades.

(2) 20 to 26 million people will have gained coverage by 2023, many of them with government subsidies that make the purchase possible and many of whom will use medical services they would not have without coverage, thus staying healthier and more productive. (Estimates of this health and productivity gain are as yet not translated into a quantifiable economic benefit.)

(3) While millions of insured middle and upper income Americans are going to pay more out of pocket for healthcare than in the past, millions of newly insured lower income people are going to pay less out of pocket. (How that will evolve is still unclear and should be the focus on close scrutiny in the years ahead. Is this a fair redistributive trade off?)

Federal healthcare spending – CBO has annually since 2011 lowered its estimate of the 10-year cost of the Medicaid expansion and subsidies in the exchanges, the ACA’s main expense. Federal Medicaid costs resulting from the health care law would total $847 billion in the coming decade, down more than 20 percent from 2010 estimates (in part, of course, because many states have not expanded Medicaid as expected).

As for the subsidies, CBO released its latest projections earlier this month: $849 billion over the next decade, down from the $1.1 trillion it forecast in March 2010. In 2015, the subsidies will average $3,960 per person, down from $5,200 forecast in 2010.

Medicare spending? The government spent about $11,200 for every person enrolled in the program in 2014, down from around $12,000 three years ago. CBO now forecasts that Medicare spending will fall below $11,000 by 2017, adjusted for inflation, and stay there until 2020. (Medicare spending overall will still increase over the next decade and beyond as baby boomers flood into the program.)

A similar slow down has occurred in private sector insurance premiums. Average annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage were up just 3 percent last year, continuing a recent trend of modest increases, according to The Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey.

Now, get this! These trends—in Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurance —are occurring, CBO and CMS think, because the price of medical products and services, as well as the volume of those services, are not going to increase as much as they previously thought over the next decade. That’s due to forces described in the next section, intimately tied to the ACA.

Payment and delivery system reform. Talked up for more than a decade, payment and delivery system reform are at long last gaining real steam.

In February, HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell announced that by 2018 half of Medicare fee-for-service payments would be paid under contracts with incentives to manage quality and costs, up from 20 percent in 2014 and zero prior to the ACA.

Private sectors payers are ramping up their payment and quality reform efforts, too, as documented by the group Catalyst for Payment Reform. According to its latest report, 40 percent of commercial in-network payments are now tied to performance or designed to cut waste.

The bold HHS target could sharply accelerate the implementation of ACOs, bundled payments, and other alternatives to fee-for-service—if HHS/CMS gets its act together on these initiatives and providers stop balking. (In 2014, for example, just 3 percent of hospitals, medical groups and other entities that were approved to participate and prepared for bundled payments—220 of roughly 6,690 organizations—went ahead with the new payments, according to a report in Modern Healthcare. And while ACOs have generated savings, these have been slight to date.)

Hospitals are under pressure in multiple ways to cut costs and improve quality, most notably in the ACA-affiliated Hospital Value-Based Purchasing and the Readmissions Reduction Programs. And they have begun to do it. The Cleveland Clinic says it cut expenses by roughly $500 million in 2014, by reducing unnecessary tests, supply costs, and implementing efficiencies in care and administration, according to a profile of the hospital system this month in The New York Times.

In 2013, some 150,000 fewer people were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of an initial hospitalization than in 2012—bringing the rate of such admissions to around 18 percent of Medicare patients. That’s almost 2 percentage points lower than a few years ago. (Some 2 million patients are still re-hospitalized each year, however, costing Medicare $26 billion of which an estimated $17 billion is preventable. So, progress, yes, but slow.)

At the same time, fewer Americans are losing their lives or falling ill due to hospital-acquired conditions, like pressure ulcers, infections, falls and traumas. These are down 17 percent since 2010. Preliminary data show that between 2010 and 2013, there was a decrease in these conditions by more than 1.3 million events. As a result, 50,000 fewer people lost their lives and $12 billion in health spending avoided.

By 2016, HHS wants 85 percent of Medicare hospital payments to be subject to the value purchasing and readmissions programs.

Physicians have gotten the message, too—on reducing unnecessary, inappropriate and wasteful care. In droves, they are abandoning practice ownership and agreeing to affiliate with hospitals and health systems that can help them track performance and quality.

Physician organizations have joined the effort. Since its inception in 2012, for example, the Choosing Wisely initiative, organized by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, has come to encompass 70 physician specialty groups representing 500,000 doctors. The groups have made some 150 recommendations to reduce inappropriate tests and treatments.

Changes in consumer incentives and behavior. Consumers are finally becoming more discriminating healthcare shoppers. They’re tracking their medical expenses more carefully. They seek to avoid unnecessary care. They don’t want to be hospitalized if that can be helped. They are opting for hospice care at end of life. They want to know their treatment options. They ask for generic drugs. They are angry about medical billing practices. They no longer put their doctor on a pedestal. They are sick of system complexity. They ask tougher questions.

The (possibly) bad news is that some of the above is happening because consumers are paying more out of pocket for care, courtesy of higher deductible, co-pays and co-insurance. As well tracked by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a rapidly growing proportion of insurance plans now offered through employers and sold through the exchanges have deductibles of $1,000 or more.

Conservatives applaud this, arguing that it was long past time to enhance consumer’s “skin in the game” and force them to spend healthcare dollars more wisely. Democrats and liberals worry that the shift is hurting middle-income families, and that we have a frog in the hot water problem. As employers and insurers turn up the heat on out-of-pocket costs, we could reach a negative tipping point of too much deferred (needed) care.

At the same time as they are increasing deductibles and co-pays, insurers are reinventing managed care in ways that could hurt consumers—namely, narrow networks, especially popular in the exchanges. Exchange-based plans are also paying doctors and hospitals less than employer-based plans, according to a CBO analysis. CBO’s recent caution: “Many plans will not be able to sustain such low provider payment rates or such narrow networks over the next few years,” putting “upward pressure” onpremiums in the exchanges.

On the other hand, narrower networks have the potential to enhance price and quality competition in a medical marketplace that has sorely lacked it. Pitting health systems and medical groups against each other for low-cost, high quality care was, despite everything you’ve ever heard from Republicans in Congress, a hoped- for outcome of the ACA.

Unfortunately, insurer competition is still not as robust as hoped for. A 2014 GAO report found that enrollment in the individual, small group and large group markets is concentrated among the three largest insurers in most states. They have some 80 percent of enrollment in 37 states. In more than half of those states, a single insurer had more than half of the total enrollees.

Final note: if the reduction in healthcare spending growth is sustained, it will reduce annual federal budget deficits and long-term federal debt, on top of the deficit reduction the ACA was always forecast to achieve. (Yes, in case you forgot, the ACA was always projected to reduce the deficit.)

In that context, the latest attempt by Republicans in Congress to repeal the ACA—in the Senate budget resolution last week—includes an almost incredibly disingenuous provision to allow lawmakers to ignore the fact that the repeal would add $210 billion to the deficit over 10 years.

The ACA’s hoped-for affect on costs, competition and care delivery appear to be materializing. It’s still too early to declare full victory on affordability in all its dimensions, however. Healthcare in the U.S. is still too expensive. There’s still too much wasteful spending. Prices are excessive. Here’s wishing the ACA lives on for another 5 years, and beyond, to help solve these problems.

Steven Findlay is an independent journalist and editor who covers medicine and healthcare policy and technology.